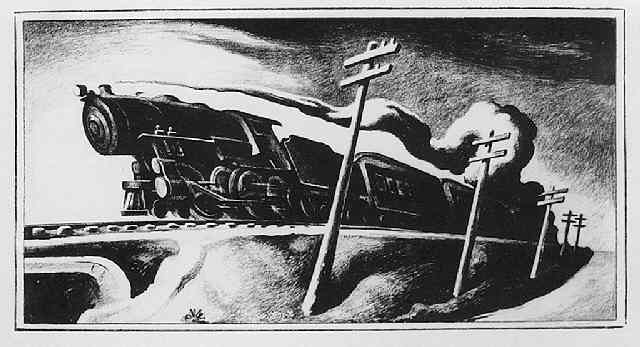

Express Train (Going West)

At the risk of seeming to indulge in hyperbole, I think this is one of Benton’s very finest drawings, ranking with the best drawings by him I have seen. Indeed, if one were choosing one drawing by him to sum up his artistic achievement, I can’t think of a better example. I would not hesitate to rank this piece as one of the most outstanding drawings of the 20th century by any American artist.

The image is both modern, with a sense of movement and energy that recalls the Italian Futurists, and wonderfully American in its evocation of the great open spaces of the American West. Other great American artists such as Reginald Marsh made wonderful representations of trains, but this image is in a class by itself. Figures such as Marsh wonderfully capture the externals of a steam locomotive, but Benton in some magical way seems to become the train. In his hands it becomes a living thing, the embodiment of life, force, energy, and the American spirit. Benton himself wrote nostalgically of trains of this sort:

Steam powered railroad trains were fascinating all my life. The Diesels have never had the same interest for me chiefly because their driving mechanisms are not visible. You don’t get any emotional kick out of what you can’t see.

As you know, this is a preparatory study for Benton’s lithograph Going West, which was issued by the Ferargil Galleries 1934, in an edition of 75, and is often regarded as Benton’s finest print. The dimensions of drawing and print are identical, indicating that the drawing is a direct preparatory study, surely also made in 1934. Personally, I like the drawing a little better than the print, although both are marvelous. It’s more forceful in its expressive exaggerations, such as the way the front of the locomotive pushes ahead of the rest of the train, and the use of line is freer, more expressive, and less self-conscious. I particularly love the virtuosity of the single wiggling line that represents smoke coming from the front stack, as well as richly evoked volume of the the swirls of the smoke in the background, and the way that Benton really dug into the paper to capture the dark shapes of the cowcatcher and the wheels of the train.

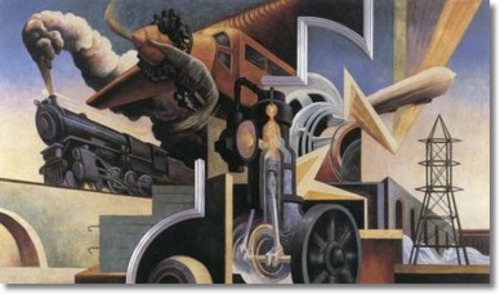

There’s an ancestry to this train in slightly earlier works by Benton. It’s most direct prototype is the similarly elastic streamlined train in the panel Instruments of Power–the central defining image of his mural America Today, 1930, the painting which made Benton famous and which is often considered his masterwork. The distinct forward thrust of the body of the train closely relates to a still earlier work, a drawing by Benton of a train exiting from a tunnel that was reproduced in The Dial, the most important modernist magazine of its period, in July 1925.

Throughout his life, Benton was fascinated by trains. As he wrote in his autobiography, An Artist in America:

My first pictures were of railroad trains. Engines were the most impressive things that came into my childhood. To go down to the depot and see them come in belching black smoke with their big headlights shining and their bells ringing and their pistons clanking gave me a feeling of stupendous drama, which I have not lost to this day. I scrawled crude representations of them over everything.

There are various accounts of these early train drawings, now lost. One of Benton’s friends recalled him chalking a train some 100 feet long on a concrete drain. Benton’s sister Mildred described to me a drawing of a train that went up the stairs to the attic of the family home. Benton himself recalled an early drawing of a train that was destroyed:

When I was six or seven years old our house was newly papers in some light cream-colored paper. We had a stairway which went around a landing from the lower hall to the second floor. My first mural consisted of a long freight train in charcoal which went up this stairway on the new paper. It began with the caboose the foot of the steps and ended at the top with the engine puffing long strings of black smoke—because of the heavy grade. The kind of appreciation afforded this early effort was the first intimation I received of the divergency of view on the subject of mural decoration. The question of appropriateness, which later on and on other occasions I was to hear a lot about, was then brought up for the first time. Decision in this case was against me and, after a good lecture my labors were obliterated with bread crumbs.

Remarkably, while these works are lost, there is one surviving drawing of a train from this early period. Made during a stopover in Vinita, Oklahoma, it was saved by a family friend, Mrs. Saunders, and is now in a private collection in Kansas City. Made when Benton was only nine years old, in 1898, it shows a complete mastery of perspective, and is so accurate that a Kansas City railroad expert was able to identify the specific locomotive that Benton drew, MKT number 14, the so-called Katy Flier, manufactured by the Pittsburgh Locomotive Company in 1870.

As I’ve indicated this is a preparatory study for Benton’s print Going West, and, in addition to its artistic merit it is interesting for what it reveals about Benton’s working methods. In his later years Benton drew directly on the lithography stone, with only cursory preparatory studies, but in this instance he clearly made an exact working drawing, executing it on tracing paper so that he could flip the image when he executed the print, in order to take into account the reversal that comes about when you execute a lithograph.

I feel confident that the work is not a copy but an original drawing for many reasons. For one thing, it differs from the final image in ways that indicate that it’s a true working drawing, not a copy. This is made by an artist who understands the significance of every element and detail. Also, the execution is marvelously free and wonderfully expressive—not qualities easy to fake. There are passages of great delicacy and other passages, such as some of the lines of shading on the embankment, which are executed very boldly, with Benton’s very distinctive and impatient scribble-scrabble line. While I don’t know the whole provenance of the drawing, it’s also encouraging that it was included in the exhibition “Art on Paper” at the Weatherspoon Art Gallery, University of North Carolina at Greensboro. This took place in 1977, when Benton was still alive, and at a time when it seems altogether unlikely that a drawing of this sort would have been faked.

Image List:

1. Express Train (Going West)

c. 1930-34, Lithographic crayon

Initialed lower right

2. Express Train (Going West)

1934, Lithograph

12 3/8 x 23 3/8 inches

3. Instruments of Power

America Today panel

1934, Oil